Bartók’s cycle of six string quartets are must-know works. Like Haydn’s and Beethoven’s efforts in the genre they span almost his whole compositional life. They are masterful compositions and groundbreaking in their sonority and harmony. We have always been lucky that they have been readily available in excellent recordings; in fact, each decade of recorded history since the war seems to have produced at least one library choice.

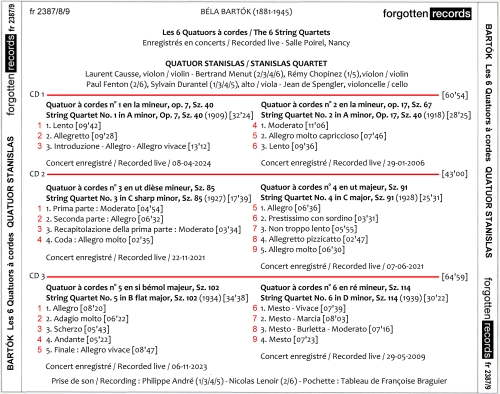

The Quatuor Stanislas’ cycle has just been released on Forgotten Records and contains the works in live performances recorded over an eighteen-year period. They are based in Nancy in France and I assume that they are named after Stanislaus I, the last Duke of Lorraine (Nancy is the principal city of the region), the exiled Polish monarch whose tenure in Nancy brought a flowering of enlightenment and culture to the city around the 1750s.

The Stanislas has made many a record in its long partnership, often exploring interesting, rarer repertory like Sauguet and Ropartz. For Forgotten Records they have assembled a decent collection which includes the unusual and mainstream music. We reviewed their Beethoven set favourably when it came out five years ago.

I have always loved Bartók. From Kossuth in 1903 to the Viola Concerto of 1945 there are so many treasures and at least 25 individual works that I would argue with anybody are out-and-out masterpieces. As I was born near Manchester and grew up around the region, I soon discovered he had a connection to the city. As a twenty-two-year-old, he was invited to the Hallé in 1904 for a performance of Kossuth by the great Hans Richter. He played some piano works in the concert, too, and I believe spent several days in Didsbury being pampered and playing his excellent Piano Quintet with and for some enlightened Mancunians. He made the long journey from the Hungarian plains to darkest Lancashire the following season, too.

Bartók’s works of those days are heavily influenced by Brahms, Reger and Strauss, as you would expect. By 1908, however, when he penned his first quartet, he had discovered a wider range of influences, thanks to his friend Zoltán Kodály. Debussy’s music had a profound impact and his burgeoning interest in ethnomusicology was soon all-encompassing. Bartók travelled around Europe and even into North Africa collecting folk songs and often recording them on his phonograph.

String Quartet No. 1 dates from 1908. The next quartet was written between 1915 and 1917, war years in Europe. Bartók’s String Quartet No. 3 is from ten years later. By then, his great stage works had been produced, he had explored chromaticism in works like the violin sonatas and had written the perfect Dance Suite. There was a period in the mid-1920s of creative silence, but that difficult third quartet came after it, and shortly after the writing of his Piano Concerto No.1. The fourth string quartet followed swiftly in 1928 and the superb fifth in 1934. From 1936 to the onset of the second world war in 1939 saw Bartók write works like Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta, Sonata for two Pianos and Percussion, Contrasts and the Violin Concerto No.2. His final quartet followed them. After this the composer made his sad exile to America, arriving at the end of October 1940.

In reviewing this particular cycle of quartets, I have paired each one with a favourite of mine from my shelves. I must report truthfully, that in all six cases, I preferred the studio recording with which I was making my comparison. Nonetheless, I sincerely enjoyed the Stanislas’ accounts of the great works and was glad to have spent the week with them.

For String Quartet No. 1, I returned to the Takács Quartet in their acclaimed Decca recording which was made in the Summer of 1996. The Decca sound was always superb on these records and still sounds stunning to my ears. The Takács pace the long first movement with its grieving, yearning lines perfectly. Their tone is full and rich, and it fairly throbs with passion. Of course, we know that in writing this piece, Bartók’s relationship with Stefi Geyer had been broken off and he felt it deeply, evidently. The Stanislas Quartet paint an impassioned picture, full of heart and conviction. Laurent Causse isn’t afraid of using vibrato and the cello of Jean de Spengler takes the role of the aching heart to full effect.

The first quartet is a work that moves from darkness to light. The second movement allegretto has plenty of twists and turns and it can feel quite episodic in some performances, which is what I experience here with the Stanislas. Although it is taken quite slowly, the pulse is at least maintained throughout, and the tonal polish is impressive. As they move into the finale, begun with musings on cello framed by an audience of excited upper voices, the Stanislas are in fine ensemble. When the rustic dance finally gets underway, there are some lovely touches and moments of genius. The Stanislas are not afraid to linger awhile and create some special effects. Bartók’s newfound compactness and tonal palette influenced by the French school is put to great use in this movement. The folk songs of the pentatonic Magyar style he had collected and was immersed in nightly can be heard undiluted, too. This finale of 1908 is surely the greatest single span of music Bartók had written up to this point in his life.

Accomplished as the performance by the Stanislas is, it cannot compete with the splendid Takács version of nearly thirty years ago. The airy sound, coupled with the faster pace of both second and third movements brings a focus I miss in the newer version. The stamping rhythms are wilder, too, and the tensions that bit more urgent. The overall playing time for the Takács is over three-and-a-half minutes quicker.

The No.2 is perhaps Bartók’s most accessible string quartet. The format is three movements, like the first quartet, and it goes slow-fast-slow. I thought I would turn to the Tokyo Quartet on DG for this work. This was the first work they recorded in their award-winning cycle. It was recorded as long ago as 1975, although the complete set most of us first heard it on, was not seen until 1981. In this piece we hear the last echoes of Bartók’s late Romanticism. It is an impassioned, very personal work and I have always enjoyed the care and precision the Tokyo Quartet bring to it. They are expansive in tempi and bring great sensitivity to the outer movements. The older DG sound is a little dated now, but those of us who “found” these pieces with these players won’t grumble. Of course, since 1981 there have been plenty of versions of this quartet that are technically just as accomplished and rhythmically far more dramatic, I concede that the Quatuor Stanislas, in their oldest recording on the set from 2006 gives a red-blooded performance of this seminal work. There is a nice sway to the pulse in the first movement and a controlled build-up of tension. Bartók’s structure is not revolutionary, and the sonata principles are easily recognised. Thematically, it is easy to get a hold on, and those searching, reaching themes are thoughtfully phrased by these superb French musicians with some distinguished quartet playing in this first section. The earthiness of the spiky fast motifs in the scherzo is a real feature that the Stanislas accentuate. More alive and urgent than the old Tokyo Quartet reading, it will impress many, I am sure. They are also memorable in their sultry trio which doesn’t hang around too long. The final lento movement has that sad, wartime, nostalgic feeling that I hear in British works of the era composed in those days of the trenches. The Hungarians fought a gruelling campaign on the Eastern campaign in conditions just as awful as in the West. Bartók must have read daily about his compatriots on the Isonzo front and I hear this in his finale, a musical response perhaps akin to that penned by Vaughan Williams and others in those same times. This performance by the Stanislas is, I think, one of the finest on the records.

Bartók’s Quartet No. 3 is severe and uncompromising. It is written in a very compressed manner and most performances come in around the fifteen-minute mark. Although the music is seamless, you could divide it into four, I suppose, in a slow-fast-slow-fast arrangement. I pulled down an underrated set by the Hagen Quartet on DG made in two halves in the mid-to-late 1990s and issued (but not for long) by DG around 2000. Both groups are similar in prima parte but the Hagens are fleeter in the livelier seconda. The final coda is begun famously with sul ponticello bowing. Truthfully, though, there has been all manner of sound effects employed before that in this innovative work. It is all very intense and breathless. The Hagen gives it what it requires, capitalising on its modernity and their virtuosity is marked. The Quatuor Stanislas is recorded very closely in this work. The sonics certainly display the remarkable tonal spectrum the players create vividly, but it is all a bit too bright and full on. The thematic cells that Bartók writes in this work are often short and brief, just a few notes long. It is what he does with them that is so impressive. I appreciated hearing the motifs change and swell in Stanislas’ more measured reading of the turbulent seconda parta and the ensuing calmer ricapitulazione. The important inner voices are captured clearly, too. I have heard more fluent and exciting codas, however – not least, I have to say, my comparative version.

Bartók’s fourth uses a five-movement arch structure of pleasing symmetry. I is mirrored by V, II by IV, with movement III being an example of the composer’s night music style. For maximum contrast in this work, I compared the Stanislas Quartett with the Emersons. Their DG recording won the Gramophone “Record of the Year” in 1989. It was one of the first CD sets I ever purchased. I remembered their No. 4 being fast and furious. The timing was only 21:22. Compare that with 25:31 on the newer record.

These two middle quartets are easy to admire, but hard to love. The themes are stark and bare and the drive so hard at times. The first movement is uncompromising; I always feel battered by it. The second movement, a scherzo, is a relief but still uneasy listening – again, fast and unrelenting. The melodies are chromatically conceived and reveal their gifts under duress. When we arrive at the central plateau, it is with some relief. Jean de Spengler’s solo for the Quatuor Stanislas is as always full bodied and rich. This is the Bartók I love best. As we traverse the palindrome of the quartet down again, we next arrive at the second scherzo, written in pizzicato entirely. Finally, the springing, angular heavy rhythms of the first are echoed at the last. Like the Quartet No. 3, we are treated to vivid sound, up close. Ensemble is not quite as tight in the finale as in the earlier movements of the piece; notwithstanding, the group is committed and play the piece with total conviction.

The Emerson String Quartet, faster in all five sections of the work, never seems to be under any difficulty. Their sound is focussed, sharp and coloured. Their technique, admired so much at the time, is still hugely satisfying. Just listen to them in that spectral second movement – stunning playing. The engineered sound is wonderful, too. There must be many a music lover who got to know the quartets from this venerable set and it must surely be one of the Emerson’s best records.

For the majestic Quartet No.5, I have chosen to listen to the Stanislas alongside the most recent CD set of the quartets I own, namely the Jerusalem Quartet on Harmonia Mundi. In fairness, it is not that recent ; it was recorded in 2019 and its companion disc, four years before that. They are special versions of the works for me, though. The fifth quartet dates from 1934 and finds the composer in rude health, musically speaking. Here there is melody, colour, life and beauty of form. For many, including me, this is Bartók’s finest quartet. Moving like the fourth in an arch, this time fast-slow-scherzo-slow-fast.

The Stanislas Quartet performance dates from 2023. It is highly accomplished and vital in execution. The clever sonata style first movement is Beethovenian in its vision and intent, if not its “inverted” construction. The adagio is dreamy and tonally inspired. It gets a splendid run-through here, as fine as any. The central scherzo is marked alla bulgarese. It starts with charming arpeggios winging chirpily over a pizzicato cello line. The trio is genius; no one else in the twentieth century could possibly have written this music, infused as it with so many folk elements, juxtaposed with such rhythmic invention and harmonic wizardry. Dissonances and shades of night music haunt the atmospheric andante. The Quatuor Stanislas pace the piece slowly, allowing the chilly effects ample time to resonate and build gradually and it works well. It is a similar story in the last movement, composed on a large scale to mirror the first. It is really a huge rondo, but the intensity builds in a way Beethoven would recognise, I think. We might recall the journey Beethoven took us on in his fifth symphony maybe. Like Quartet No.2, this is one of the glories of the Stanislas Quartet’s cycle. The Jerusalem Quartet also play the work marvellously well. The refined sound stage we get from Harmonia Mundi is spacious and not boosted or highlighted in any way. It is one thing I love about the set. The whole cycle from this group is of the highest quality, very polished. Like the Stanislas, they do take their time to create their effects. I am sure, despite his quite literal markings in the score regarding tempi and timings, Bartók would have adored the finished results.

Bartók’s last string quartet did not arrive seamlessly. The time of its composition was a momentous one for all Europeans and also personally for the composer and his family. He lays himself bare in the work in a way he does not in any other quartet. It is a sad piece; in fact, each movement is prefaced with a motto entitled mesto developed differently each time. It is an emotionally deep work, and I hear a resigned withdrawal from the world in it, graded in stages as we move through each of its four movements. The last is utterly desperate. For my final comparison I selected the Belcea Quartet in their EMI set from 2007 to pit against the Stanislas. Timings are almost identical for the first three movements, but the Belcea Quartet are a good deal quicker in their finale. I really enjoyed the Stanislas Quartet again. I do hear some intonation issues, especially in this finale but the reading is touching and deeply felt. The EMI recording is well worth hearing too. The Belceas at the time were riding high and they are a crack unit technically. The sound is first rate, too.

All the performances by the Quatuor Stanislas end with applause. The audience are not too intrusive at all, the odd cough apart. There are occasional platform noises but nothing serious. If you are looking to complement your existing library, though, and gain some fresh insights into these amazing works, you could do worse.

Philip Harrison